At this time of the year, farmers are prepping their haymaking equipment and are planning their haymaking strategies. The goal for dairy farmers is to start making hay as early as possible (in Delaware County, this is mid-May) to capture the highest possible quality of forage. Dairy farmers then aim to make subsequent forage harvests about one month apart. This forage is typically either made into haylage or baleage. This cutting strategy maximizes the quality of their forage harvest in order to support the milk production of their cows.

But should a beef, sheep, or goat farmer attempt to do the same? Well, the answer is that depends. Non-dairy livestock have lower energy demands for significant periods of the year. Most livestock farmers birth their animals in the spring and then graze the livestock on pasture for the rest of the summer. By fall, the young are often weaned and sold. That leaves us largely with our breeding animals that enter winter in a ‘maintenance’ state. These animals do not need energy dense stored forages during most of the winter. In fact, if they did eat “dairy cow quality” hay, they could get fat.

Making really high quality hay is expensive and time consuming. And if our beef, sheep and goats do not need high quality hay for the winter feeding season, should we go through the extra cost and effort to make it? In fact, a later cut hay is a better match to the nutritional needs of beef cows or non-lactating sheep or goats. Here are two potential cost saving opportunities you may want to consider:

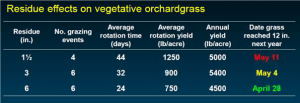

- Reduce the number of times you cut hay each year on any given field and start later. You can get the same quantity of forage in the year but with less tractor time, fuel, and labor. (Think two cuttings instead of three or four cuttings.)

- It is more likely that you will be able to make dry hay. The cost of plastic ranges from about $3.00/round bale in in-line wrapping systems to almost $7/round bale when you wrap the bales individually. Assuming you have a place under a roof to store your dry round bales, this is money and time you might be able to save.

What about our still growing youngstock, late gestation ewes or goats with twins, or early lactation ewes and goats with twins? These animal classes all need high quality forages or an energy supplement such as grain. So, if you are feeding hay or baleage to these classes of animals, you may still need to make or purchase some “dairy cow” quality hay for them.

My advice – make a hay harvest plan to create the forage inventory you need to adequately meet the nutritional needs or your animals. Want help in doing this? Email Rich Toebe at rrt43@cornell.edu.